(From left to right): Preston Pangle, Dr. Xiaomin Chen, Dr. Kevin Knupp, John Mark Mayhall, and Kiahna Mollette are UAH atmospheric scientists studying different characteristics of hurricanes to better predict the intensity of hurricanes before making landfall.

JUN 02, 2023 | Liz Junod

Scientists from The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH) Department of Atmospheric and Earth Science are preparing to study hurricane characteristics to better predict the intensity of these storms before they make landfall. Hurricane season officially started June 1.

Dr. Xiaomin Chen, assistant professor in the department, is collaborating with Dr. Kevin Knupp, director of UAH’s Severe Weather Institute – Radar and Lightning Laboratories, to focus on near-surface localized wind gusts. Two students in the department – graduate student Kiahna Mollette and undergraduate senior John Mark Mayhall – will each work with a NASA program to study, respectively, lightning and cloud formation.

Greater accuracy in forecasting hurricane intensity will enable atmospheric scientists to better inform the public of the potential devastation and how to prepare for it.

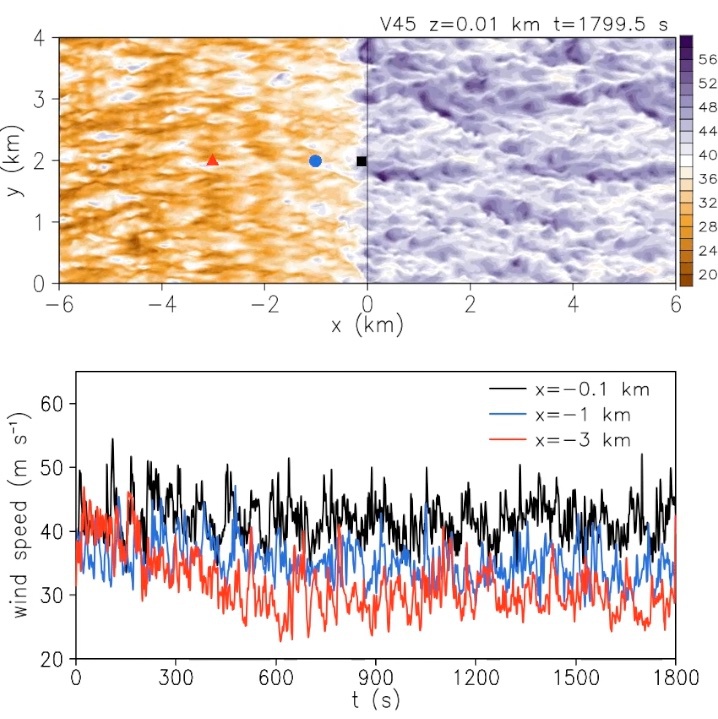

Courtesy Xiaomin Chen

“Very little data has been collected on near-surface localized wind gusts, as it’s not permitted for aircraft to fly that low to the ground,” says Chen.

Researchers must be on the ground in the path of a landfalling hurricane to collect this data.

Chen and Knupp plan to deploy UAH’s Mobile Atmospheric Profiling Network fleet of research vehicles to study hurricanes anticipated to make landfall along the Gulf Coast. The Mobile Atmospheric Profiling Network is a National Science Foundation-funded requestable facility that is part of the Community Instrument and Facility suite.

UAH’s research vehicles are equipped with instrumentation to collect real-time localized wind gust data before and during a hurricane making landfall.

To assist with these deployments, Chen and Knupp will form a team of undergraduate and graduate researchers from the department and train them to take proper safety precautions.

Mollette and Mayhall will work with the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center Short-term Prediction Research and Transition Center (SPoRT) program in hurricane rapid intensity research under the advisement of NASA SPoRT civil servant Dr. Patrick Duran.

“Currently, it’s difficult to determine what the intensity of a hurricane will be at landfall,” Mollette says.

The National Hurricane Center defines rapid intensification as a change in sustained winds of 30 knots, or 35 miles per hour, within 24 hours. The National Hurricane Center is working to improve its hurricane intensity forecast as hurricanes can rapidly intensify in less than 24 hours.

Mollette uses data from NOAA’s Geostationary Lightning Mapper aboard the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite East to study the brightness of lightning flashes that occur in the inner eyewall of a hurricane and its relationship to hurricane intensity. The brightness of a lightning flash is known as optical energy.

“By studying the relationship of optical energy and hurricane rapid intensification, we may be able to observe a hurricane intensifying in near real time, thus allowing operational weather forecasters to provide more lead time to the public of how strong a hurricane will be once it makes landfall,” Mollette explains.

Mayhall is studying whether bands of cirrus clouds generated from a hurricane’s outflow is a precursor to rapid intensification.

“When a hurricane begins to strengthen,” he says, “a lot of air is evacuated from the eyewall and pushed outward in all different directions, creating what’s called an outflow. This outflow of air can create bands of cirrus clouds.”

Mayhall says the tricky part of his research is that bands of cirrus clouds can be produced by hurricanes in multiple ways, not just from outflows.

Chen, Knupp, Mollette and Mayhall will be closely monitoring the potential of hurricanes for the next six months through the official end of hurricane season on Nov. 30.